For Children to Learn, We Must Teach them in Languages they Understand

Ajay Pinjani, Nadia Naviwala and Mohsin Ali

A three-year study by TCF finds that using familiar languages when children are young and then gradually introducing foreign languages maximizes comprehension and fluency.

It is no secret that primary education in Pakistan is not delivering the results that government policies, the donor community, and non-profit organizations envision. Millions of children in the country are not in school. And yet, millions more who attend school suffer the effects of a flawed education system. For years, researchers have pointed to the myriad of challenges that the country’s education system faces – defective examination systems, poor physical facilities, lack of teacher quality, low enrollment, large-scale dropouts, corruption, poor management and supervision, lack of research, and policy implementation failures, to name a few.

Undoubtedly, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these issues, and further limited access to education.

In a country with over 70 native languages, a critical impediment is the language used as the ‘medium of instruction.’ In Pakistan, parents demand ‘English-medium education’ for the many academic and professional doors it can open for their children. But because the majority teachers in Pakistan are not proficient in English, it is only textbooks that are in English while teachers and students speak local languages in the classroom. Schooling is reduced to rote memorizing textbooks that children do not understand, hindering intellectual growth and the joy of learning.

What Happens when Children are Taught in a Language they do not Understand

In a kindergarten classroom in Islamkot, a tehsil (township) in the Tharparkar desert in Sindh, a child named Mehtab eagerly writes his name in English on the blackboard. He does a perfect job – carefully forming each letter of his name and then reading it loudly. However, it is not until the research team rubs off the last two letters of his name and asks him to read that he gives them a blank stare.

Mehtab has rote learned his name, just as he is expected to rote memorize his textbooks.

This meaningless memorization of information happens in classrooms across Pakistan, where children’s language and cultural context is not taken into consideration. It has led to a crisis – one where children who regularly attend school can’t read or write a simple sentence in any language albeit being in school for several years.

While many valid questions arise from such a conundrum, research shows that using an unfamiliar language as the medium of instruction in the primary years’ curriculum in Pakistan hurts children’s ability to learn to read and understand concepts. There is overwhelming consensus amongst educationists around the world that learning should be in a language that students understand – usually the language that they speak at home, referred to as their ‘mother tongue’. This research also establishes that children who develop strong language skills in their own language are better able to learn foreign languages like English later on.

Scouring the World to find a Localized Answer

TCF partnered with the Thar Foundation in 2018 to develop a mother tongue based multilingual education (MTB MLE) model for schools in the desert region of Tharparkar, Pakistan. While Sindhi is the provincial language in Tharparkar, over 13 sub-regional languages are used by the local population – these include Dhatki, Marwari, Katchi, Oadki, and Parkari. In Tharparkar, it is typical for children in one school to speak several different mother tongue languages.

While previous research has primarily addressed the need and impact of MTB MLE programmes, there is limited guidance available on how to design such programmes for schools with multiple mother tongue languages. As a result, while many practitioners, policy makers, and even experts acknowledge the importance of education in the mother tongue, it does not seem feasible to implement.

TCF’s first research report on education policy builds on findings from academic literature on MTB MLE, a study of global MTB MLE programs, interviews with over 130 practitioners, policymakers, and academics worldwide, and a socio-linguistic survey carried out in parts of Tharparkar.

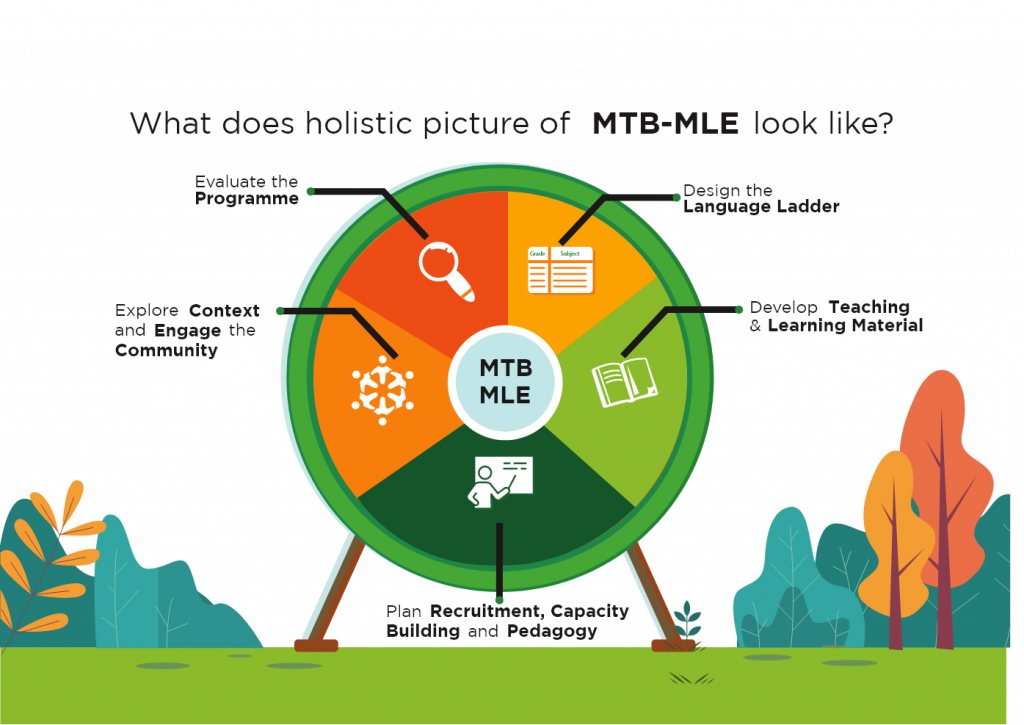

The report, “Finding Identity, Equity, and Economic Strength by Teaching in Languages Children Understand,” is an effort to bridge the gap between theory and practice by offering guidance on designing MTB MLE programmes for linguistically heterogeneous contexts. It outlines guiding principles for the development of context-specific language ladders which dictate the proposed language journey of a child’s education, beginning with the most familiar language in the early years and gradually incorporating additional languages.

Both researchers and those who have implemented MTB MLE have observed this models’ benefits on three critical fronts:

- Cognitive understanding: strengthens students’ conceptual clarity and enables original expression

- Academic utility: builds the foundation for the student to learn both academic subjects and unfamiliar languages effectively

- Social belonging: enables the development of confidence and self-esteem, as well as parental involvement in a child’s education

This initiative takes into account decades of scholarship and introduces an unprecedented mode of education planning – one that places the child at the center of their learning experience.

Policy decisions on language are only the first step towards implementing an effective MTB MLE system. These decisions should be accompanied by: mapping the socio-linguistic context of target communities (what languages do children understand? What languages do teachers speak?), designing language progression plans, developing teaching and learning materials, training and coaching teachers (such as to teach literacy and build vocabulary), planning for recruitment, and finally, effectively evaluating programmes.

Testing the new approach in Tharparkar

In early 2020, TCF began testing its research-based MTB MLE model in 21 classrooms, starting with pre-kindergarten and kindergarten. Initial surveys found that two languages dominated day to day conversations: Dhatki and Sindhi. To cope with the challenge of multiple mother tongue languages in a classroom, TCF shifted its emphasis from ‘mother tongue language’ to ‘most familiar language.’ The aim was to transition all students to the ‘familiar’ regional language of Sindhi, which was commonly spoken and to which all children had oral exposure, by the end of grade 1.

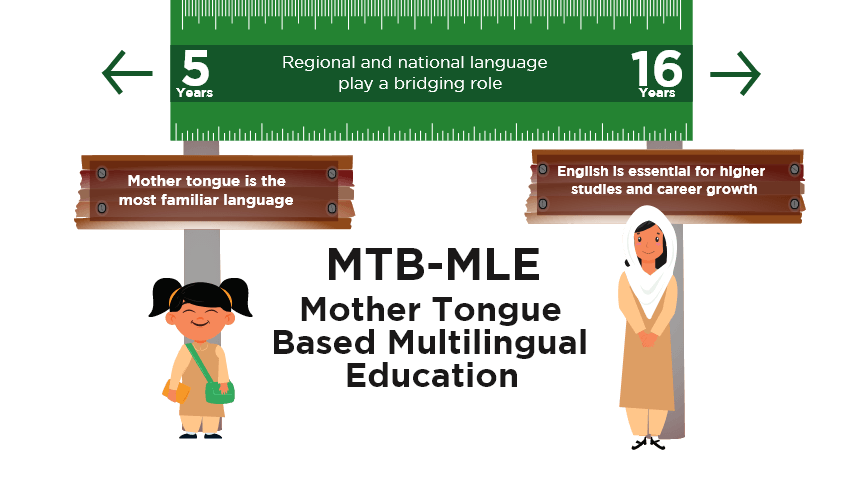

In total, students had to transition through fluency in three or four languages over the course of their education: from diverse mother tongue languages (Dhatki and Sindhi) to the regional language (Sindhi), then the national language (Urdu), and then to an international language (English). All higher education in Pakistan is in English, making English a necessity.

TCF sequenced the introduction of languages based on its research as follows. The transitions are gradual, emphasizing bilingual and multilingual instruction.

Build Foundations in Mother Tongue and Regional Languages from Pre-Kindergarten until Grade 3: The goal is to strengthen foundations (reading, writing, listening, and speaking skills) in the mother tongue. Where multiple mother tongue languages are spoken, a familiar language can be determined with an aim to transition all students to that language by the end of grade 1.

Gradually Transition to National and Foreign Languages in Grades 4 through 7 using Multilingual Instruction: Learners will experience a gradual transition from most familiar language as the medium of instruction to a second language as the medium of instruction through a bilingual or multilingual teaching and learning model.

Rely on a National or Foreign Language as the Medium of Instruction for Grade 8 Onwards: For Grade 8 and beyond, learners will fully transition to using the national or foreign language as a solo medium of instruction to acquire proficiency and access knowledge available in that language.

TCF has already started a gradual graded roll out of this model in TCF schools supported by the Thar Foundation in Tharparkar. It will continue to be adjusted based on learning from the pilot.

Anticipated Challenges

The MTB MLE initiative poses some challenges, even within the limited context of the 20+ schools TCF is introducing this in.

First, many parents fear that absence of education in English-medium jeopardizes future opportunities for their children in a national economy that prioritizes English. To address this, the design of MTB MLE systems requires the inclusion of feedback from parents, guardians, and community members.

Second, the design relies on a linear, incremental approach. This can pose a challenge for children joining school at the middle or higher levels. Additionally, students who drop out to attend another school with a different curriculum will also face challenges. To alleviate these potential shortcomings, bridge or accelerated learning programmes will need to be incorporated into the design.

Third, given the challenge of multilingualism, countries like Pakistan should give thought to developing a cadre of teachers who are able to provide language instruction, in the mother tongue as well as second, third, and fourth languages.

Conclusion

For children who grow up in multilingual communities around the world, diversity has become a handicap rather than a source of strength. In Pakistan, the response to linguistic diversity has been a blunt insistence on the national and foreign languages, Urdu and English. This has made quality education impossible for the majority of Pakistani children who grow up without exposure to these languages.

Unlike a lot of research that precedes this study, TCF does not just insist on mother tongue based approach to education. Instead, it provides pragmatic recommendations for how Pakistan, and countries like it, can provide mother tongue based education in contexts where there are many and then build bridges to help students acquire the foreign languages that they need to succeed.

Download the Mother Tongue Based Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE) Research Report